A significantly abridged version of this essay (also: without footnotes) appeared in my column Detour Ahead in Jazz Podium (December/January 2024/2025).In the spring of 1958, George Wein and Marshall Brown auditioned 17 young European musicians for a big band that was to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival that same year. For many of the participants, the two-month trip was a formative experience.

The idea

In 1958, Albert Mangelsdorff was selected during an audition to play with the International Youth Band at the Newport Jazz Festival. George Wein, the director of the festival, which had been founded just four years earlier, had been toying with the idea for a while and, after a financially successful festival in 1957, was able to convince the festival board that such an ensemble would be a good fit for Newport, that it would promote the event and at the same time show that American jazz had become an international language [1]. The valve trombonist and music educator Marshall Brown had performed with great success at the festival the previous year with the Farmingdale High School Band, which he conducted. Wein invited him to join the board to oversee educational projects in the future [2], first, an international youth orchestra with members from as many European countries as possible, both on this side and beyond the Iron Curtain. The board granted them a budget of US$30,000 to finance their trips to Europe, the auditions on site, flights and accommodation for the selected musicians, and an extended rehearsal period [3], Instead of a fee, the young participants would receive a kind of daily allowance [4]. At the same time, Brown and Wein set to work. Wein contacted experts, mostly journalists, who were to organize the preliminary rounds in fifteen countries and also spread the news in their respective scenes. In Italy, for example, his contact was Arrigo Polillo, in Denmark Erik Wiedemann, in Poland Józef Balcerak, in Belgium Carlos de Radzitzky, in France Charles Delaunay, in the Netherlands Paul Acket, in Spain Esteban Colomer Brossa, in England Pat Brand, and in Germany Joachim Ernst Berendt. Meanwhile, Brown commissioned musicians Bill Russo, Adolph Sandole, Jimmy Giuffre, and John LaPorta to write compositions for the ensemble, which did not yet exist [5].

Auditions

Brown took a year's leave of absence from his teaching position for the project [6], which gave him the freedom to travel through Europe with George Wein in February and March 1958 to audition and cast the final lineup of their dream band [7]. Willis Conover, host of the jazz programs on Voice of America, which introduced many fans and musicians, especially in the countries behind the Iron Curtain, to the latest American developments, announced the two's trip on his program on February 14, 1958. [8]. However, the idea of a kind of pan-European big band [9] did not initially catch on everywhere, and so the German media reported on a truly international line-up in which “for example, a trumpeter from France, an alto saxophonist from Japan, a tenor saxophonist from Germany, and a drummer from Australia” were to play together [10].

Between 15 and 30 musicians were invited to auditions in no fewer than 15 countries [11] on the recommendation of local experts. Marshall Brown tested them in a first round for their musical accuracy—the idea was to put together a big band that was capable of playing advanced arrangements by renowned composers. The second round focused on their ability to improvise. Brown had prepared a kind of evaluation sheet for six criteria: musical proficiency, improvisation, intonation, sound, phrasing, and technical mastery of the instrument [12]. The applicants were allowed to play a few pieces of their own choice with a provided rhythm section, then Brown, whose interest was apparently mainly in the brass section [13], gave them sheet music written by himself, John LaPorta, or Bill Russo “to see what they could do with it.” [14]. The musicians did not receive any results; each was dismissed with an “Awful nice” [15] and a few tips, so Brown was certain: “Every one of the participants in the auditions left as a better musician.” [16]

First, the two talent scouts, accompanied by Marshall Brown's wife, flew from New York to Lisbon [17]. Their visit was significant enough to be reported on Portuguese television [18]. Wein recalled the audition in a report for the Boston Herald: "The club was loaded with enthuisiasts but most of the musicians were too shy to try out for the band. After a while they relaxed and we finally had our pick from about fifteen candidates. We heard a good drummer but our choice will probably be either a pianist or a trumpeter who did not even bring his trumpet to the audition. We had to go to a club where he was working where he played for us a beat-up old trumpet that looked like it came through the Spanish Civil War." [19] He was José Manuel Magalhães, then 29 years old, who at the time of the audition was playing trumpet in the country's radio orchestrar [20]. From Portugal, they traveled to Barcelona, where Wein and Brown were particularly impressed by pianist Tete Montoliu, who was ultimately not selected because the plan was to choose only one musician from each country and there was no second pianist [21]. Instead, the 29-year-old alto saxophonist Wladimiro Bas Zabache from Bilbao, who had been at home in the jazz clubs of Madrid since the early 1950s, won the race [22].

From Barcelona, Wein and Brown flew to Geneva, where, however, they were unable to find suitable musicians for the band. The journalist Demètre Ioakimidis had apparently only advertised the audition in French-speaking Switzerland. As a result, the only person who showed up was a pianist who was not good enough, even though he insisted that there was no other professional pianist to be found in the whole country. George Gruntz, who ultimately won the race, had learned about another audition a few days later in Milan through saxophonist Flavio Ambrosetti [23]. At the time, Gruntz had a permanent job as a car salesman and didn't take the audition very seriously; he had never heard of Brown and Wein, and as he later recalled, the two seemed to have no idea about the local scene. They boasted that they had already listened to more than 600 young European jazz musicians, and after the Geneva fiasco, Brown complained that Switzerland might have cuckoo clocks and chocolate, but no jazz [24]. Gruntz knew at least one of the arrangers, Bill Russo, with whom he had taken a correspondence course in arranging [25]. After reviewing all the candidates, Gruntz won the race mainly because Joe Zawinul, whom George Wein would have preferred, was out of the question, as the two talent scouts in Austria had already found a tenor saxophonist in Hans Solomon. Wein then championed Zawinul a year later when he needed a letter of recommendation for his visa to study at Berklee College [26]. In Milan, in addition to Gruntz, drummer Gil Cuppini was also selected, who at 34 was one of the older members of the band [27].

In Germany, Joachim Ernst Berendt, Werner Wunderlich, and the German Jazz Federation had spread the word about the preliminary round. There were two auditions, one at the Frankfurt Jazzkeller and the other “during an SWF television broadcast” in Baden-Baden, where the original idea was to have “the winners of last year's German Amateur Jazz Festival” perform [28]. This plan was still based on an average age of between 16 and 25 [29], which Wein and Brown had apparently quickly revised upwards during their trip, probably because they realized that it would be difficult to find musicians in this age group who could handle the complex arrangements they had commissioned. At the first rehearsal in Frankfurt's Jazzkeller, most of the musicians were actually older than the originally targeted age: Albert Mangelsdorff (29), Dusko Goykovich (27), Wolfgang Schlüter (25), Peter Trunk (24), and Rudi Sehring (27). Mangelsdorff and Goykovich then had another chance to perform the next day in Baden-Baden, together with Stefan von Dobrczinsky, Helmut Brandt, Karl Berger, Umberto Arlatti, and Eberhard Stengel, the latter two then members of the Modern Jazz Group Freiburg [30]. Mangelsdorff particularly remembers the audition in the jazz cellar and how “inappropriate” he found it “to be examined in front of a packed audience while sight-reading” [31]. But the other musicians were not exactly thrilled about the school-like exam situation either [32].

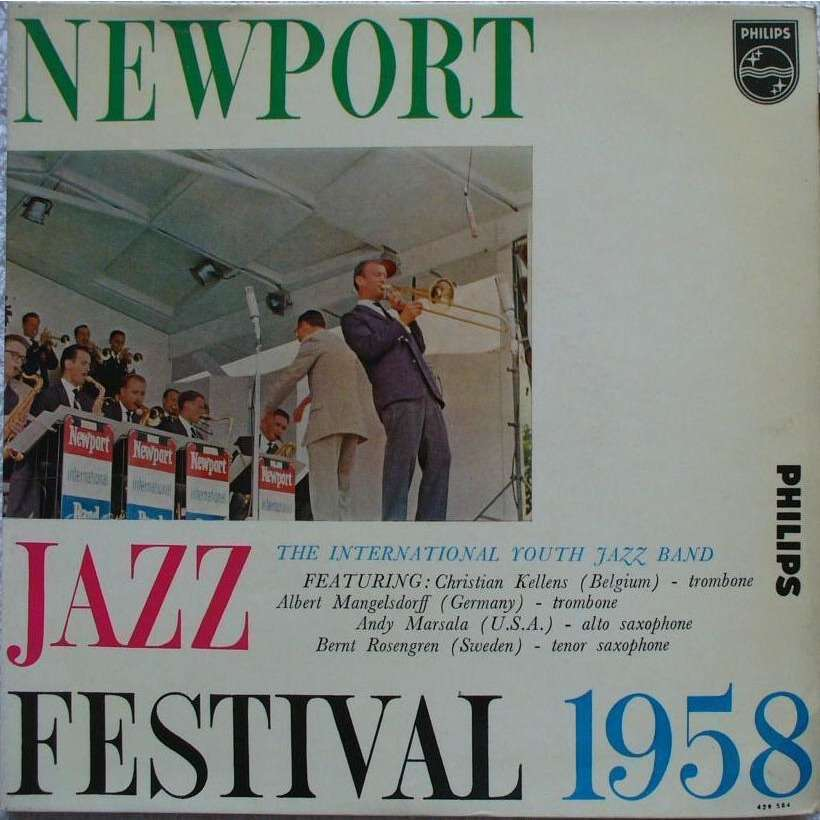

In Amsterdam, the audition took place at the Bellevue Theater; within the scene, it was referred to only as the “Battle of Newport” [33]. Bassist Ruud Jacobs won the race here, but Belgian trombonist Christian Kellens, who at the time was playing in Kurt Edelhagen's big band alongside Dusko Goykovich, also made the grade [34]. Ronnie Ross, who was selected as the British representative on baritone saxophone, like other musicians, already had numerous recordings to his credit. At the time of the audition in February 1958, he was involved in a recording with John Lewis, “European Windows” [35].

In Paris, George Wein had actually been looking for an alto saxophonist for the band. Pierre Gossez, who was under consideration, already had other plans, so Charles Delaunay recommended trumpeter Roger Guérin instead of an alto saxophonist. After an audition, sight-reading, and a solo chorus, he joined the band [36]. Guérin was born in Saarbrücken in 1926 and had already played in numerous renowned bands in 1958, performing with American soloists such as Rex Stewart, Don Byas, Kenny Clarke, and James Moody. In composer André Hodeir's Jazz Groupe de Paris, he had become familiar with complex, advanced arrangements, and Claude Bolling, Martial Solal, and Michel Legrand also called on him whenever they needed a trumpeter [37]. In Vienna another alto saxophonist was being sought, as Hans Salomon is convinced, remembering: "Joe Zawinul on piano and Carl Drewo on tenor saxophone were much more experienced than I was, but those instruments were already taken [38].

Palle Bolvig was selected as lead trumpeter for the band during auditions in Copenhagen [39]. Bolvig was a fan of Maynard Ferguson and was already well known enough before Newport to play the high notes in an orchestra scene in the American film “Hidden Fear,” which was shot in Copenhagen. For a while, he worked as a high-note specialist in the Ib Glindemann Orchestra, from which he was granted leave for the Newport gig [40]. During rehearsals, Swedish musician Bernt Rosengren must have been particularly moved by the band's arrangement of “Swingin' the Blues,” based on Count Basie's recording with Lester Young, which had been an eye-opener for him [41].

In fact, however, the second tenor saxophonist, Jan Wróblewski, sounded even more strongly influenced by Young than Rosengren [42]. Wróblewski came from Poland, one of two countries behind the Iron Curtain, alongside Czechoslovakia, where Wein and Brown were looking for musicians for their International Youth Band – Goykovich, who was in the band for Yugoslavia, had been cast in Germany.

In Warsaw, the audition organized by the editors of Jazz magazine took place at the Philharmonic Hall [43]. As Jan Wróblewski recalls, the most important Polish pianists of the time were there, including Krzystof Komeda, Andrzej Trzaskowski, and Andrzej Kurylewicz. Many of the jazz musicians were already eliminated during the test of their knowledge of musical notation. In Poland, the weekly newsreel reported on the audition; Brown and Wein can be seen on stage, while a rhythm section accompanies Jan Wróblewski. At the end of the report, Brown enthusiastically declares: “They have the same spirit as Americans, which is a wonderful thing.” [44]

In Poland, Józef Balcerak, Wein's local contact and editor of the magazine Jazz, had asked his American colleague to help him leave the country. He was Jewish, and although the war had been over for more than ten years, his fear had never left him. Wein was sorry, but he couldn't help him [45]. Guitarist Gabor Szabo had left Hungary in 1956 during the Hungarian uprising and settled in the United States as a political refugee. He was cast together with another Hungarian student at Berklee College, where he studied [46]. In Prague, Wein and Brown chose Zdeněk Pulec, a trombonist who was equally versed in jazz and classical music and whom Marshall Brown described as a “second Jay Jay Johnson” [47]. There are different explanations for the reasons for his non-participation. One is that Pulec's father was against the trip because his son was still too young [48]. The official reason given was that there was a scheduling conflict due to a concert at the conservatory where Pulec was studying [49]. A third explanation points to difficulties caused by the Cold War [50], and George Wein recalls in his autobiography problems with the Czech authorities, who did not issue the necessary papers [51]. As replacements, Wein and Brown chose two trombonists, Kurt Jarnberg from Sweden and Erich Kleinschuster from Austria, which somewhat disrupted their original concept of having only one musician from each country.

Incidentally, the only American in the band was 16-year-old alto saxophonist Andy Marsala, whom Marshall Brown had discovered at the age of 12 and whom John LaPorta had been teaching since he was 13, writing the “Jazz Concerto for Alto Sax” especially for him. Marsala had already performed with the Farmingdale High School Band in Newport the year before. He was technically proficient on his instrument, but at that point he was not yet able to improvise, so Brown asked LaPorta to write down solos for him, which he memorized and played during the performance as if he had invented them himself. This went on for two years, LaPorta recalls, until Marsala asked him if he would mind if he played his own solos in the future. But what surprised LaPorta most was that Marsala's own solos sounded exactly like LaPorta's—without the teacher ever having given him improvisation lessons, he had internalized his stylistic vocabulary to such an extent that even LaPorta had difficulty telling the difference between Marsala's approach and his own [52]. As Brown's protégé, Andy Marsala remained a member of the Newport Youth Band until 1960 [53].

The trip to Europe was a significant learning experience for Wein and Brown. Brown was amazed at the number of good musicians he encountered in Poland, of all places, behind the Iron Curtain [54]. During the auditions, he noticed that musicians in Europe seemed to copy a lot. When presented with sheet music, he said, they would play every note, never leaving one out—he had never really realized before that this freedom in dealing with music was typically American [55]. Wróblewski, on the other hand, peeked at one of the evaluation sheets during the audition and read the following comment about Komeda: “Like Monk, but not his music.” Wein in particular recognized that the participants in the Newport project would play an important role in the development of jazz in their respective countries on the way to an independent European language of jazz [56]. This first extended trip gave him a glimpse of the diversity of the different European jazz scenes; it also enabled him to make contacts that would benefit him in his later work as an agent and festival organizer [57].

After Wein and Brown had heard between 600 and 700 applicants from all over Western Europe and at least two countries behind the Iron Curtain, they reviewed the evaluation forms, decided on a lineup, and on March 25, 1958, sent telegrams to 17 musicians from 16 countries informing them that they would be traveling to the United States for a month and a half. Brown told the press that he would have liked to take more musicians with him. Based on the quality of the auditions, he said, he could have easily invited 13 trumpets, 9 trombones, and more [58]. [58].

During the preliminary stages, the project, in which Wein saw a diplomatic benefit, was still running under the working title “The Tower of Babel Band.” However, the festival board opposed such an Old Testament band name and insisted on the more sober “International Youth Band.”

Rehearsals in New York

The journey alone was an adventure for the musicians. None of them had ever been to the USA before. Originally, they were supposed to meet in Paris [59] and then travel together by ship to New York, where rehearsals were to begin [60]. Then the plans were changed, and all the musicians were invited to Brussels, where they were expected by Marshall Brown and Willis Conover at the airport [61], which had been newly opened especially for the World's Fair [62] and from where they flew to New York with a stopover in Canada [63]. Dusko Goykovich had given up his place in the Kurt Edelhagen Orchestra for the trip because Edelhagen wouldn't let him go. “You have a good reputation here,” Edelhagen told him, “what do you want in the USA?” Goykovich recalls that Edelhagen wanted to fire him if he went over there even for just a few weeks [64]. Two of the musicians did not make it to Brussels in time and arrived separately: Jan Wróblewski had received his transit visa too late and Wladimiro Bas Zabache had missed his connection from Madrid [65]. Together, they were supposed to spend the next month and a half in the US, first four weeks rehearsing in New York, then a week in Newport, then another week in New York.

Upon their arrival at New York's Idlewild Airport, the excited new orchestra members were greeted by the Tony Scott Quintet [66], which also included trombonist Jimmy Knepper [67]. Some of the musicians took their instruments out of their cases and sat in. They drove to the New York Beverly Hotel on Lexington Avenue [68], which was not far from the rehearsal room [69] and where they every six of them had to share a room. Before the trip, the musicians had already provided their clothing sizes so that they could be outfitted with matching band uniforms in the US [70]. Instrument maker Conn also provided them with new instruments [71]. Hans Salomon recalls that on their very first evening, they went to Birdland, where Johnny Griffin was playing [72].

Rehearsals began the next day, daily from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. [73], interrupted only by short breaks for meals. The arrangements commissioned by Marshall Brown were new to everyone in the band. For some reason, however, it was only now that Brown realized there might be a language problem. Not all of the musicians spoke English well enough; Wróblewsky and Magalhães didn't speak any at all [74]. Brown complained that the only musician he could talk to was the British musician Ronnie Ross [75]. It helped that Dusko Goykovich spoke seven languages [76], and Christian Kellens [77] and George Gruntz were also helpful. Albert Mangelsdorff and Hans Salomon also put their experience in GI clubs to good use in translation tasks [78]. In any case, the language problems led to initial delays, as Brown reported: “At the first rehearsal I spent 20 minutes getting across to the musicians that I wanted them to go back to letter 'B' in the arrangement.” [79] You can probably imagine it a bit like Chinese whispers: Brown's instructions to one of the saxophonists first went to one of the trombonists, who passed them on to a trumpeter, only to end up with the confused saxophonist [80].

The rehearsals weren't easy either, as George Gruntz recalls: “Marshall Brown was a friendly, very dedicated music teacher, but he just wasn't a born bandleader; the rehearsals dragged on forever, so that at some point our nerves were frayed and we even ended up arguing.” [81] Brown had mostly dealt with young people up to that point, but now he was faced with musicians who already had careers behind them. He was irritable and hectic, recalls Salomon, a nervous, chaotic person [82]. Rosengren and Mangelsdorff complained that he treated the band members, who were all between 25 and 35 years old, like schoolboys [83]. Not everyone was happy with the name of the band either; they simply felt too old for an “International Youth Band.” Ruud Jacobs sums it up: Marshall Brown was simply too emotional and far too hectic to lead such a band. [84] And Albert Mangelsdorff adds somewhat more diplomatically: “Marshall Brown is certainly a very capable bandleader – nevertheless, I would like to say that I didn't learn much new.” [85]

Not all of the musicians liked the arrangements they were presented with either. Wróblewski recalls how interested they actually were in the African American side of jazz, only to be presented with sound experiments, for example by Bill Russo. They had the most fun with an arrangement by Gerry Mulligan, which he himself rehearsed with them in one of the first rehearsals, but then Marshall Brown decided not to include this particular piece in the program [86]. There may have been various reasons for this. Wróblewski speculates that Mulligan made Brown look pale as a bandleader [87]; but Brown had also fallen out with George Wein when he publicly demanded that musicians have more say in the programming of the Newport Festival [88]. Goykovich and Ronnie Ross made no secret of their dislike of Brown, and Albert Mangelsdorff even recalls that some of the musicians tried to have Brown replaced by Gerry Mulligan [89].

So no Mulligan; instead, the repertoire ultimately consisted of arrangements and original compositions by John LaPorta, Adolph Sandole, Arif Mardin (who was studying at Berklee College on a Quincy Jones scholarship at the time), Bill Russo, Jimmy Giuffre, and Marshall Brown himself. These arrangements were different from what the musicians had played at home, recalls Ruud Jacobs, “but after a few rehearsals the band sounded pretty good” [90]. There were also other opinions. Bernt Rosengren, for example, didn't particularly like John LaPorta's pieces, and Albert Mangelsdorff summed it up: “Many of the pieces we were given to play didn't really appeal to us.” They were pieces “that just didn't swing or were too compactly arranged, leaving no room for improvisation.” [91] . Perhaps it would have been better, Mangelsdorff thinks, “if we had been allowed to play pieces by European arrangers that suit us better.” [92]. In his letter of acceptance to the musicians, Wein had even offered them the opportunity to bring their own arrangements [93], but if they did, none of them made the cut.

The first public appearance before Newport took place on the Arthur Godfrey television show, which was broadcast during prime time. A few days later, there was a performance in front of journalists, who particularly enjoyed the solo performances of tenor saxophonist Bernt Rosengren, Albert Mangelsdorff, and Dusko Goykovich [94]. At the press conference, the musicians praised Brown, as was to be expected, and he in turn emphasized how hard-working, enthusiastic, and understanding the European band members were [95].

After rehearsals, the band hit the jazz clubs of New York. They hung out with colleagues such as Mulligan, Cannonball Adderley, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Art Farmer, Johnny Griffin, John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Bill Evans, Oscar Pettiford, and Tony Scott, who took them to concerts and introduced them to the scene [96]. Roger Guérin met up with fellow countrymen who were living in New York at the time: pianist Francy Boland and saxophonist Tony Proteau [96]. Ruud Jacobs spoke with Paul Chambers about double bass strings and was grateful for how extremely helpful Cannonball Adderley was [98].

Roger Guérin recalls a set by the Miles Davis Sextet at Small's Paradise, the Thelonious Monk Quartet at the Five Spot, and Slide Hampton's arrangements for Maynard Ferguson [99]. ”For a month and a half, we visited every jazz club we could find," says Jan Wróblewski. "We spent a whole week in Harlem, listening to Miles' sextet with Adderley, Evans, and Coltrane, the ‘Kind of Blue’ band. (...) The only club I didn't manage to get into at the time was the Village Vanguard." [100] Miles had already heard of the European musicians; he even knew Dusko Goykovich personally, which earned him additional respect from his bandmates [101]. Ruud Jacobs, on the other hand, felt that Miles was hostile toward all white people [102]. Bernt Rosengren remembers the tenor saxophonists particularly well: Johnny Griffin in Thelonious Monk's band, Benny Golson with Art Blakey, and Booker Little with Max Roach [103]. Wróblewski listened to Maynard Ferguson's big band, the Sonny Rollins Trio, and the Hi-Los at Birdland. At the concert by Ferguson and the Mitchell-Ruff Duo at Birdland, the musicians were even introduced to the audience, but were not allowed to perform according to the statutes of the American musicians' union [104]. So they played less often in clubs, but instead, as Albert Mangelsdorff recalls, at jam sessions "in the private homes of fans and musicians. Even in the hotel where we were staying," then with two clothes brushes on a newspaper instead of drums [105].

Wróblewski recalls hearing Miles at least seven times during that period, but he was most impressed by another set that they stumbled upon rather by chance because, after twelve hours of rehearsing, they were too tired to look for music and simply sat down for a beer in a bar around the corner. Suddenly, a trio featuring Eddie Lockjaw Davis, Shirley Scott, and a drummer appeared on stage, “the best school of black jazz” [106]. Ruud Jacobs was also there and remembers sitting at a table next to Billie Holiday, whom he later took home together with Tony Scott. As they said goodbye, Scott called out to her, “Don't forget, we'll see you in three days for the string recordings!” Three days before her legendary “Lady in Satin” date – “I wish I'd had my cell phone with me,” jokes Jacobs, “I should have taken a selfie with her.” [107].

Newport

The International Youth Band performed twice at the Newport Jazz Festival, once with their full rehearsed repertoire on Friday afternoon and once with a shorter set on Sunday evening, just before Louis Armstrong and his All Stars. Before them, John LaPorta with his quartet and Jimmy Giuffre with his trio (Bob Brookmeyer, Jim Hall) performed on Friday [108]. Willis Conover, who hosted the entire evening, then introduced the European musicians one by one, each of whom went up to the microphone and said “thank you” in their respective national languages [109].

While the band sounded fresh and enthusiastic on a sunny Friday afternoon, the musicians had to contend with high humidity on Sunday. In the humid weather, it was almost impossible to see the stage from the back rows, reports Eric T. Vogel [110], explaining the effects on the musicians: “Not only did the musicians feel uncomfortable in this ‘cold steam bath,’ but the instruments also suffered: the tension of the drums and strings slackened and the mouthpieces stuck to the lips.” [111]

Despite all the adversities, the band sounded quite good after such a short collaboration and in view of the demanding arrangements, Albert Mangelsdorff concluded in retrospect [112]. Eric T. Vogel particularly liked Jimmy Giuffre's “Pentatonic Man” (which unfortunately did not make it onto the album of live recordings released by Columbia). Vogel writes that it was particularly noticeable in the improvised parts that this was not an American band, not because, as he writes, they “were particularly bad, but because they seemed more primitive and inhibited as soloists than their American colleagues.” [113].

The musicians took the opportunity to listen to all the other colleagues they met in Newport. It started at the Viking Hotel, where they were staying “next door to Miles, John Coltrane, and all the other stars,” as Dusko Goykovich recalls [114]. They joined in jam sessions whenever the opportunity arose [115]. And, of course, they attended the other bands' concerts. Albert Mangelsdorff, for example, recalls that he liked Duke Ellington much better than Benny Goodman's band, which George Wein had put together especially for the festival [116]. On Sunday, many of them had been looking forward to the performances by the Sonny Rollins Trio, Horace Silver, and Thelonious Monk. However, Marshall Brown called them in for a final rehearsal at exactly that moment because George Wein had decided at short notice that the band should play a piece with Louis Armstrong at the end of their performance, who would then close the festival with his All Stars in an almost two-hour set [117].

Wein, who wanted to promote the International Youth Band as a unique selling point for this edition of the festival, asked Brown to arrange “On the Sunny Side of the Street.” The International Youth Band only played the arrangement; Armstrong was in the foreground as trumpeter and singer. Jan Wróblewski remembers the rehearsals with Armstrong as the highlight of the trip: “He was such a wonderful, outgoing guy, cheerful and friendly to everyone, but at the same time your legs would shake when you talked to him. If you ask me, the piece with him was probably our best performance, simply because everyone in the band was so tense.” [118] Decades later, George Gruntz still raved about the feeling of accompanying Armstrong with his distinctive, world-famous voice. What you hear: The band begins, then Armstrong immediately joins in with the theme chorus on the trumpet. At the beginning of the first vocal chorus, he asks for a glass of water. The band plays arranged accompanying parts, and one can imagine how Gruntz must have felt playing his Billy Kyle-esque fills between Armstrong's phrases. In the second vocal chorus, the band accompaniment seems a little stiff at first, then follows a bridge written partly in double time, which leads into a solo break by Armstrong, which he ends with the ad hoc phrase “Swiss Kriss ... gets it Jack.” [119]. A trumpet chorus follows, and it is easy to understand Roger Guérin, who was particularly impressed by Armstrong's self-confidence and his complete rejection of clichés [120]: Satchmo simply improvised until the end of his life [121]. Guérin was so impressed by this that when asked about his favorite trumpeter, he, who was actually considered a representative of modern jazz, always named Armstrong first. His lack of star airs had already impressed the musicians during rehearsals, after which Satchmo handed each member of the band a bag of the very Swiss Kriss he had praised in his vocal break, a laxative he swore by: “Leave all the bad things behind you!” [122]

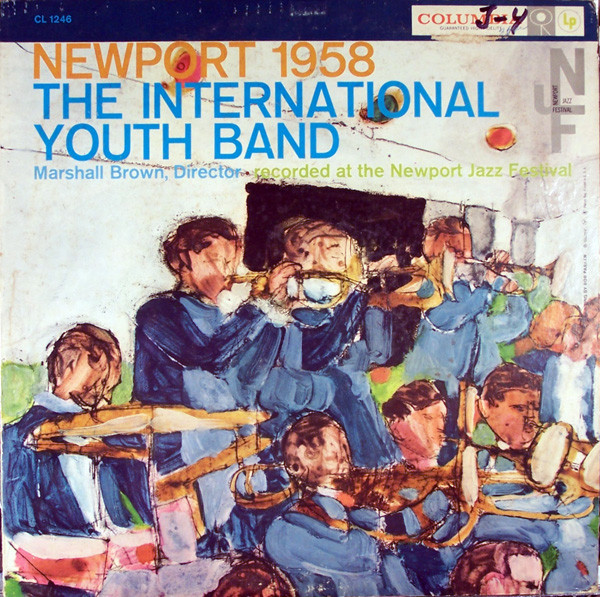

The recording with Armstrong and the International Youth Band was not released until decades later on an LP. The pieces without Armstrong (except for Giuffre's “The Pentatonic Man”), on the other hand, were released the following year on the Columbia label, which had committed to documenting the project on LP, for which Brown was able to select the best versions from both performances in Newport [123]. [123].

Despite all the criticism of Marshall Brown as bandleader, his “Don't Wait for Henry” is one of the arrangements that gives the musicians the most room for improvisation. Bernt Rosengren, Dusko Goykovich, Albert Mangelsdorff, Jan Wróblewski, and Kurt Jarnberg showcase their different musical characteristics. Rosengren's solo explains why he was considered one of the band's best soloists by critics and John LaPorta [124], whereas Wróblewski clearly remains oriented towards the sound of Lester Young.

The 17-year-old American alto saxophonist Andy Marsala takes center stage in John LaPorta's arrangement of “Don't Blame Me” and in his “Jazz Concerto for Alto Sax.”

The big band provides only a sonic backdrop, and one can sense the dissatisfaction of the musicians, who were known at home primarily for their solo work. There was a reason why Albert Mangelsdorff had already left Willy Berkings' dance band, which was admittedly far less hip. Otherwise, the arrangements are based on the current big band language in the USA, a little Basie, a lot of Woody Herman, a touch of Stan Kenton.

Adolph Sandole's arrangement of “Too Marvelous for Words” evokes the West Coast sound that was also popular in Europe. Rosengren shines with a solo; Mangelsdorff's very short solo part seems somewhat helpless, and Goykovich also struggles to break free from the tight framework of the arrangement.

Basie's “Swingin' the Blues” was orchestrated for the big band by Marshall Brown and LaPorta and once again reveals both the strengths and weaknesses of the band. In short, the rhythm section is unable to generate any real driving force; the solos, in this case by Rosengren, Goykovich, Mangelsdorff, Ronnie Ross, Roger Guérin, and Christian Kellens demonstrate the improvisational qualities of the young musicians. The problems of the rhythm section reflect a shortcoming that American soloists repeatedly reported when they were looking for a European rhythm section for a tour in those years: rhythm sections that were both driving and maintained the balance of swing were simply a rarity in Europe. In the recordings, these difficulties can be heard particularly in Cuppini's playing, but Ruud Jacobs was also a better soloist than big band player, as Bill Coss notes in his review [125].

Arif Mardin's contribution is his arrangement of “Imagination,” whose theme is played by Christian Kellens and in which Gabor Szabo also shines with a short solo contribution.

The program concludes with Bill Russo's two-movement “Newport Suite,” subtitled “A Blues and a Dance,” a sophisticated work that draws on the Third Stream of the time while also paying homage to Duke Ellington's “Crescendo and Decrescendo in Blue,” which was a highlight of the 1956 Newport Festival. However, Russo's composition is meticulously crafted down to the smallest detail, so that even the short improvised parts – only Hans Solomon is given a solo that can really be perceived as such – hardly have a chance of being perceived as the soloists' own contribution. After his return, Mangelsdorff complained that the arrangements were far too experimental for an untrained band and had hopelessly overwhelmed them.

In any case, the recordings confirm what the reviews of the time also attest to: Bernt Rosengren, Dusko Goykovich [126], and Albert Mangelsdorff [127] were regarded as outstanding soloists in the ensemble. After the concert, German-born journalist Eric T. Vogel asked musicians and critics for their opinions. Miles Davis thought the arrangements were terrible; for him, Hans Solomon and Dusko Goykovich stood out as soloists. Tony Scott had accompanied the band throughout the rehearsal phase and regretted that the arrangements did not allow the soloistic qualities of the musicians to shine through more clearly. He liked Jacobs, Mangelsdorff, Goykovich, and Ross, and he thought the band sounded better than Benny Goodman's. Ross and Roger Guérin were praised by Nesuhi Ertegun, who said the ensemble's sound reminded him of Woody Herman. Nat Hentoff, who also praised Ronnie Ross, felt that the arrangements showed Marshall Brown's ability to rehearse them with this ensemble in such a short time. Ross and Goykovich were the favorites of Swedish journalist Bosse Eckberg. Marshall Stearns, finally, was discreetly reserved in his response, pointing out that he was not a critic but a historian, and concluding with a wink: “Ellington has nothing to fear!” [128]

The orchestra did not receive a particularly favorable response, according to the German magazine Jazz Echo, but Albert Mangelsdorff, Bernt Rosengren, Ronnie Ross, and Christian Kellens received positive reviews [129]. John Hammond saw Brown as the real problem, considering him “anything but an inspiring bandleader.” [130] Joachim Ernst Berendt also complains that Brown commissioned arrangements from the very arrangers “who write the most difficult big band scores being written today.” Simpler arrangements and more room for improvisation would have been better [131]. Bill Russo disagreed, unsurprisingly. "The band was good, but they had difficulties playing together, which is perhaps in the nature of the project. After all, no European musician has our jazz background," he said [132]. Leonard Feather highlights the difference in character among the band members: “Some of the musicians looked like children, others seemed poised and mature.” [133] John S. Wilson touches on another sore point in the New York Times: “Solo improvisation did not appear to be one of their strong points.” [134] However, Wilson also attributes the band's “rather lumpy, unformed” performance to the cumbersome arrangements, of which only Bill Russo's ‘Blues’ in his “Newport Suite” stood out positively [135]. And Eric T. Vogel sums it up in the German Jazz Podium: "The basic idea was undoubtedly fascinating: the aim was to show the American audience the enormous influence jazz has on musical life around the world, and to prove this by presenting representative young musicians from all over the world in a single ensemble. (...) However, the arrangements did not meet the expectations of the band members—or rather, some musicians did not meet the high demands placed on them by the sheet music. It would certainly have been better to use European arrangements and to remove from the program those concepts that gave the musicians no opportunity whatsoever to perform as soloists. [136]

Finally, Horst Lippmann wrote a scathing review in Jazz Podium – which is not entirely understandable from today's perspective – stating that this failed project had not only “destroyed the illusions of 17 European musicians, but once again proved itself unworthy of great musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker.” [137]

Brussels

On their way back from Newport to New York, the band stopped in Boston, where the musicians listened to the Dave Brubeck Quartet with Paul Desmond at George Wein's club Storyville. Some of the musicians joined in, and years later Mangelsdorff still remembered “what ears this man has,” how harmoniously open-minded Brubeck was able to respond to him. [138]. On the last evening in Newport, Gerry Mulligan had invited the band to a party. On this occasion, Hans Salomon met Art Farmer and Oscar Pettiford, among others, musicians who would both be living in Vienna shortly thereafter [139]. Armstrong's singer Velma Middleton, who was also at the party, invited him and Erich Kleinschuster to a concert by the Armstrong All Stars on Long Island, saying they were welcome to ride along in the band bus. On the way back from the concert, they stopped in Corona, Queens, where Armstrong invited them into his house for a while. However, the jokes he told were far beyond Kleinschuster's and Salomon's English skills [140]. On the last evening of their stay in New York, Marshall Brown invited all the musicians in the band and some friends from the New York scene to a farewell party at his apartment. It turned into a long jam session, with Oscar Pettiford joining in, Gruntz playing piano, and John LaPorta playing saxophone [141].

A concert by the International Youth Band originally planned for Washington, D.C. [142] did not take place, nor did a “fortnight-long tour of the USA” that the organizers had dreamed of in advance [143]. After Newport, however, the band appeared on the Perry Como Show, which was hosted by Bob Crosby during the summer months. Jan Wróblewski was particularly impressed by the professionalism with which an arranger wrote an arrangement for the studio orchestra and the International Youth Band within 24 hours and excerpted the parts [144].

After returning from the US, the band stayed together for about two weeks. First, they played at a classic car show in Blokker, Holland [145], where 23-year-old organizer Ben Essing had recently mobilized 6,500 people for a Benny Goodman concert [146], as well as in The Hague [147]. Then, from July 29 to August 3 [148] for a week at the Brussels World's Fair exhibition grounds, where, as Brown proudly notes, they were the first jazz band to completely fill the concert hall of the American pavilion. Alongside them, the program featured jazz stars such as Teddy Wilson, Buck Clayton, Sarah Vaughan, Erroll Garner, Vic Dickenson, and Sidney Bechet [149]. The Brussels engagement was the brainchild of the State Department, which had become aware of the band when Wein asked for help with visas [150]. Here, on the initiative of Tony Scott, the musicians also met Russian musicians who took the message of this International Youth Band in Newport back with them to the Soviet Union [151]. Every night, the musicians gathered at the Chat Noir in downtown Brussels, where Swiss vibraphonist Kurt Weil played with his band, which included drummer Daniel Humair [152].

Brussels was the last opportunity to present this project not only to an audience but also to the world press. Here, George Wein was able to emphasize once again that jazz had become a global phenomenon [153]. In Newport, the press had responded favorably to all this. Although Bill Coss in Metronome had interpreted the International Youth Band as yet another “public relations measure,” he at least considered it one that had been chosen “with good taste” [154]. The reviews in Brussels, however, were not entirely positive. The idea, writes Howard Taubman in the New York Times, is certainly a great one, but even in the United States it would be difficult to bring together eighteen musicians from different parts of the country and then expect them to make musical sense in just a few weeks of rehearsals. And so, Taubman believes, the truth is that this international band was primarily a publicity stunt. “Under Marshall Brown's leadership it played pretentiously and tediously. It had no cohesion and no point of view.” [155]Taubman was not the only critic; Ralph J. Gleason even demanded, “The Newport Jazz Festival and the State Department owe an explanation to the American people for this one” – not only for the International Youth Band, but for the program at the American Pavilion in Brussels [156]. The concerts in Brussels had also been recorded, this time by the Philips record label, but unlike the Newport set recorded by Columbia, they were never released.

At the start of the project, the organizers had planned performances at the Moscow Trade Fair, but these apparently could not be realized [157]. Finally, there had been plans for the International Youth Band to tour the capitals of the European countries from which the orchestra members came in the winter of 1958, accompanied by a renowned American singer as a guest star. That didn't happen either.

Impact

Dusko Goykovich had quit his job with Kurt Edelhagen because of the Newport band and stayed in Frankfurt for a while after his return, where he founded the Jazztet with the Mangelsdorff brothers, Joki Freund, Pepsi Auer, Peter Trunk, and Rudi Sehring. Edelhagen then brought his big trumpet star, now with additional American experience, back into the orchestra [158]. For José Manuel Magalhães, too, participating in Newport was another step in his career. After returning to Portugal, he performed regularly with his quintet at Maxime, a popular nightclub in Lisbon. In November 1958, he took part in the 4th Portuguese Jazz Festival and was featured in a special on the national television channel RTP in January 1961 [159]. Palle Bolvig first returned to the Ib Lindemann Orchestra, then moved to the Danish Radio Jazz Orchestra in the 1960s, with whom he also participated in the recordings for Miles Davis' album “Aura” in 1985 [160]. Roger Guérin returned to France from the USA with the realization that the musicians in New York were considerably more professional – there was no place for amateurs there. “When I came back, I saw Paris as it is and the musicians as they are. A handful of good jazz musicians here cannot compete with the American masses, and the ‘climate’ here is not exactly conducive to innovation either.” [161]

It took Jan Wróblewski three or four months after his return to Poland to realize how the experience of this trip had changed him as a musician. Previously, Dave Brubeck, who had performed in Warsaw in March 1958, had been the pinnacle of contemporary jazz for many Polish musicians. After New York, however, Wróblewski only knew black musicians, at least according to a letter he wrote to the Polish magazine Jazz on June 22, in which he recalls how Willis Conover took him to the Black Pearl Club to see the Miles Davis Sextet [162]. “These musicians are just so incredible to me,” recalls Wróblewski, “their improvisation is so impressive, it's actually indescribable.” [163]. One insight for him was that what matters most is the almost physical experience of swing, which feels completely different when experienced live than on record. The other major realization was the affirmation of jazz as African American music, which he found so much more intense than the intellectual West Coast experiments that were considered the latest development in jazz in Europe at the time [164].

George Gruntz, who hadn't taken the auditions entirely seriously at first, recalls the band's performance as “a resounding success and a media event of the highest order” [165]. He was able to make many contacts in the US that would prove helpful for his future career, including musicians he had played or jammed with during the trip, as well as critics. In Down Beat, Dom Cerulli had compared his piano playing to an “angry Horace Silver” [166], which led to a phone call from Joachim Ernst Berendt immediately after his return to Switzerland. Gruntz says that he never “even remotely attempted to copy Horace Silver. Nevertheless, that sentence determined my career for a whole year!” Friendships had developed within the band, and over the next few years he played repeatedly with his “Newport buddies,” Albert Mangelsdorff, Ronnie Ross, Dusko Goykovich, Ruud Jacobs, and Gil Cuppini, who performed in various lineups under the name “Newport International All Stars” [167] in Switzerland, Holland, and Germany [168]. At the same time, after his return from the USA, Gruntz suffered even more than before from the attitude of European fans (and critics), who only considered local musicians worthy of recognition if they came as close as possible to an American role model [169].

Ultimately, that was also Albert Mangelsdorff's lesson from the trip. In New York, he realized that it made no sense to strive to sound like his idols, that he had to develop his own voice rooted in his own culture in order to do justice to the gift of jazz as a global musical language. The two months in the summer of 1958 were a decisive turning point for him and for numerous other musicians who had been there. On the one hand, he realized that the focus of his career would definitely be in Europe: “I wouldn't want to live in the US forever for all the money in the world.” [170] At the same time, with a newfound self-confidence, he began searching for his own path, which became apparent at the latest with “Tension” in 1963. Mangelsdorff later said of this record: “For me, it was the beginning of what I could call: From here on, it counts.” [171] – although the actual beginning of this development was the International Youth Band in 1958.

At the end of his report on the 1958 Newport Festival, Eric T. Vogel expresses his hope that the tradition of an international band would continue, as one could only learn from experience [172]. After returning from Brussels, Marshall Brown spent a few days with George Wein in Boston. The result of their exchange about the future of such an ensemble was the Newport Youth Band, for which Brown and Wein sought participants not in Europe, but at high schools in the New York area [173], and in which, instead of established musical personalities, young people were now really participating again. With the example of the Lenox School of Jazz, which had been held in the neighborhood since 1957, Wein dreamed of a nationwide organization, a kind of Newport School of Jazz [174]. He marketed the Newport Youth Band as an advertising argument for his festival by having them perform at competing events and at Carnegie Hall. Among the musicians who took their first steps in this ensemble were later renowned artists such as Jimmy Owens, Eddie Daniels, Ronnie Cuber, and Eddie Gomez. When Brown heard Maynard Ferguson's big band at Birdland in 1962, he counted no fewer than seven former members of the Newport Youth Band [175].

At the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, fights broke out among the audience, requiring police intervention. 200 people were arrested, and the festival was canceled two days before its official end. As a result, no festival took place in 1961. It was not until 1962 that George Wein was able to continue his most important festival, albeit without pursuing the Newport Youth Band idea.

Discography

-Newport 1958- : Palle Bolvig, Roger Guérin, Dusko Gojkovic, José Manuel Magalhais (tp) Kurt Järnberg, Christian Kellens, Albert Mangelsdorff, Erich Kleinschuster (tb) Andy Marsala (as solo-l) Hans Salomon, Wladmiro Bas Zabache (as) Bernt Rosengren, Jan Wroblewski (ts) Ronnie Ross (bar) George Gruntz (p) Gabor Szabo (g) Rudolph „Rudy“ Jacobs (b) Gilberto Cuppini (d) Arif Marden (arr-2) Adolph Sandole (arr-3) John La Porta (arr-4) Marshall Brown (cond).

Newport, RI., July 4, 1958

Don’t wait for Henry

Back home again in Indiana (3)

Imagination (2)

The pentatonic man

Allelujah (3)

Newport suite Op. 24 (Blues/A dance)

Too marvelous for words (3)

Jazz concerto for alto sax (1)

Don’t blame me (1,4)

Swingin‘ the blues (4)

Columbia CL1246, Philips 429584BE

Louis Armstrong and the All Stars : Louis Armstrong (tp,vcl) Trummy Young (tb) Peanuts Hucko (cl) Billy Kyle (p) Mort Herbert (b) Danny Barcelona (d) Velma Middleton (vcl)

Newport Jazz Festival, Newport, RI., July 7, 1958

On the sunny side of the street (1)

Note : (1) The International Youth Band added : Palle Bolvig, Roger Guérin, Dusko Gojkovic, Jose Magalhais (tp) Christian Kellens, Kurt Jarnberg, Erich Kleinschuster, Albert Mangelsdorff (tb) Hans Salomon, Wladimiro Bas Zabache (as) Bernt Rosengren, Jan Wroblewski (ts) Ronnie Ross (bar) George Gruntz (p) Gabor Szabo (g) Rudolph Jacobs (b) Gilberto Cuppini (d) Marshall Brown (dir)

— —

[1] Leonard Feather: New Yearbook of Jazz (1958), quoted in: Anthony J. Agostinelli: The Newport Jazz Festival: Rhode Island (1954-1971). A Significant Era in the Development of Jazz, Providence/RI 1978 (self published): 31

[2] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 179

[3] Leonard Feather: New Yearbook of Jazz (1958), quoted in: Anthony J. Agostinelli: The Newport Jazz Festival: Rhode Island (1954-1971). A Significant Era in the Development of Jazz, Providence/RI 1978 (self published): 32

[4] Eric T. Vogel: ‚Ich habe nicht viel Neues gelernt…‘ Eric T. Vogel unterhielt sich mit Albert Mangelsdorff, in: Jazz Podium, August 1958: 160

[5] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 180

[6] NN: Music: Jazz Supermarket, in: Time, 14. Juli 1958. https://time.com/archive/6806178/music-jazz-supermarket/ (aufgerufen am 25. August 2024)

[7] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[8] Rüdiger Ritter: Waffe oder Brücke? Willis Conover und der Jazz im Kalten Krieg, Berlin 2023 (Peter Lang): 460

[9] „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[10] NN: Deutsche Amateure nach Newport. George Wein plant Internationales Jugend-Orchester, in: Westjazz, 3/30 (Feb.1958): 6

[11] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[12] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[13] „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[14] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[15] „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[16] „Every musician who auditioned came away a slightly better jazzman.“ NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[17] NN: Music News. The search for young musicians in 20 European countries…, in: Down Beat, 25/7 (3.April 1958): 11

[18] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. Babel’s Band brass section. Marshall Brown’s brass section for the 1958 Newport International Youth Band. Eight promissing young European trumpet players and trombonists selected, in: www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 26. November 2012 http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2012/11/newport-58-babels-band-brass-section.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[19] „The club was loaded with enthuisiasts but most of the musicians were too shy to try out for the band. After a while they relaxed and we finally had our pick from about fifteen candidates. We heard a good drummer but our choice will probably be either a pianist or a trumpeter who did not even bring his trumpet to the audition. We had to go to a club where he was working where he played for us a beat-up old trumpet that looked like it came through the Spanish Civil War.“ George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 184

[20] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. Babel’s Band brass section. Marshall Brown’s brass section for the 1958 Newport International Youth Band. Eight promising young European trumpet players and trombonists selected, in: www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 26. November 2012 http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2012/11/newport-58-babels-band-brass-section.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[21] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[22] Hans Koert: Newport ’58: The reed section of the International Youth Band. Introducing the reed section of the Tower of Babel’s Band. Willis Conover: The Voice of America set the musical tastes of many people all over Europa, in: www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 29. Dezember 2012. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2012/12/newport-58-reed-section-of.html (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[23] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 42

[24] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 42; das betreffende Zitat findet sich bei: Whitney Balliett: International Jazz, in: The New Yorker, 5. Juli 1958: 16-17, zit. nach Rüdiger Ritter: Waffe oder Brücke? Willis Conover und der Jazz im Kalten Krieg, Berlin 2023 (Peter Lang): 461

[25] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 185

[26] George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 184

[27] Hans Koert: Newport ’58: The rhythm section of the Babel’s Band. Introducing the members of the rhythm section of the 1958 International Youth Band. George Gruntz, who recently passed away, was Brown’s second choice ….. , in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 29. Januar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/01/newport-58-rhythm-section-of-babels-band.html (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[28] NN: Deutsche Amateure nach Newport. George Wein plant Internationales Jugend-Orchester, in: Westjazz, 3/30 (Februar 1958): 6

[29] NN: Deutsche Amateure nach Newport. George Wein plant Internationales Jugend-Orchester, in: Westjazz, 3/30 (Februar 1958): 6

[30] NN: Jazz-News. Deutschland, in: Jazz-Echo, Apr.1958: 46; „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[31] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 51-52

[32] „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[33] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 63

[34] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. Babel’s Band brass section. Marshall Brown’s brass section for the 1958 Newport International Youth Band. Eight promising young European trumpet players and trombonists selected, in: www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 26. November 2012 http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2012/11/newport-58-babels-band-brass-section.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[35] Hans Koert: Newport ’58: The reed section of the International Youth Band. Introducing the reed section of the Tower of Babel’s Band. Willis Conover: The Voice of America set the musical tastes of many people all over Europa, in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 29. Dezember 2012. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2012/12/newport-58-reed-section-of.html (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[36] Roger Guérin: Roger Guérin. Une vie dans le jazz, Aubais/France 2005 (Mémoire d’Oc Éditions): 30

[37] Jordi Pujol: Roger Guérin. https://www.freshsoundrecords.com/13610-roger-guerin-albums/9-vinyl-records (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[38] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 64

[39] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182-183

[40] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182

[41] Albrekt von Konow: Bernt! „Det blir för snävt om man tänker i genrer och stilar.“ Bernt Rosengren intar en central position inom svensk jazz och är en av våra internationellt mest kända musiker. Albrekt von Konow tecknar ett intervjuporträtt i helfigur, in: Orkester Journalen, 53/2 (Feb.1985): 11

[42] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 184

[43] Krystian Brodacki: Historia Jazzu w Polsce, Krakow 2010 (PWM Edition); 204

[44] https://youtu.be/gQZj3W9BpFM (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[45] George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 185

[46] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[47] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[48] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[49] NN: The Curtain Falls, in: Down Beat, 23/15 (24. Juli 1958): 9

[50] NN: The Curtain Falls, in: Down Beat, 23/15 (24. Juli 1958): 9

[51] George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 185

[52] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 185-186

[53] Michael Fitzgerald: Newport Youth Band Discography, 24. September 2011. https://jazzdiscography.com/Artists/NYB/nyb-disc.php (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[54] Whitney Balliett: International Jazz, in: The New Yorker, 5. Juli 1958: 16-17, zit. nach Rüdiger Ritter: Waffe oder Brücke? Willis Conover und der Jazz im Kalten Krieg, Berlin 2023 (Peter Lang): 461

[55] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[56] George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 186

[57] George Wein & Nate Chinen: Myself Among Others. A Life in Music, New York 2003 (Da Capo): 185

[58] NN: Babel Band’s Birth, in: Down Beat, 25/9 (1. Mai 1958): 9

[59] NN: Youth Band Is Fretted, in: Down Beat, 26. Juni 1958: 9

[60] NN: Jazz-News. Amerika, in: Jazz-Echo, Juni 1958: 42

[61] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 64

[62] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 45

[63] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 64

[64] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 50

[65] Krystian Brodacki: Historia Jazzu w Polsce, Krakow 2010 (PWM Edition): 204

[66] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. A Tower of Babel. 27. Februar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/02/newport-58-tower-of-babel.html

[67] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 45

[68] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 50; George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 45

[69] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182

[70] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 50

[71] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. A Tower of Babel, in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 27. Februar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/02/newport-58-tower-of-babel.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[72] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 66

[73] oder, wie Bernt Rosengren sich erinnert, von morgens 9 bis abends 11…

[74] Rüdiger Ritter: Waffe oder Brücke? Willis Conover und der Jazz im Kalten Krieg, Berlin 2023 (Peter Lang): 462

[75] Max Jones: This world of Jazz. IYB preview, in: Melody Maker, 5. Juli 1958: 11

[76] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182

[77] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 183

[78] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[79] At the first rehearsal I spent 20 minutes getting across to the musicians that I wanted them to go back to letter ‚B‘ in the arrangement.“ NN: liner notes: „Newport 1958. The International Youth Band“ (Columbia CL 1246); John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182

[80] NN: Music: Jazz Supermarket, in: Time, 14. Juli 1958. https://time.com/archive/6806178/music-jazz-supermarket/ (aufgerufen am 25. August 2024)

[81] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 45

[82] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 67

[83] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. A Tower of Babel, in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 27. Februar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/02/newport-58-tower-of-babel.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024); Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 52

[84] Hans Koert: Newport ’58. A Tower of Babel, in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 27. Februar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/02/newport-58-tower-of-babel.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[85] Eric T. Vogel: ‚Ich habe nicht viel Neues gelernt…‘ Eric T. Vogel unterhielt sich mit Albert Mangelsdorff, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 160

[86] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 67

[87] Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[88] Vgl. auch Nat Hentoff: Jazz in Print, in: Jazz Review, 1/1 (November 1958): 47

[89] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 52

[90] „At first I wasn’t satisfied with the arrangements, but after a few rehearsals the band sounded pretty good“ (Ruud Jacobs. Hans Koert: Newport ’58. A Tower of Babel, in: <www.keepitswinging.blogspot.com>, 27. Februar 2013. http://keepitswinging.blogspot.com/2013/02/newport-58-tower-of-babel.html (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[91] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 52

[92] Eric T. Vogel: ‚Ich habe nicht viel Neues gelernt…‘ Eric T. Vogel unterhielt sich mit Albert Mangelsdorff, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 160

[93] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 51

[94] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[95] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[96] Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024); George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 48

[97] Roger Guérin: Roger Guérin. Une vie dans le jazz, Aubais/France 2005 (Mémoire d’Oc Éditions): 30

[98] Robin Arends: Contrabassist Ruud Jacobs, een gesprek. „Ik vond het zo spannend die snaren aan te raken en de basis te leggen voor het spelen“, in: jazz’halo. https://www.jazzhalo.be/interviews/contrabassist-ruud-jacobs-een-gesprek/ (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[99] Roger Guérin: Roger Guérin. Une vie dans le jazz, Aubais/France 2005 (Mémoire d’Oc Éditions): 30

[100] „W Nowym Jorku bywaliśmy codziennie przez półtora miesiąca we wszystkich możliwych klubach. Przez tydzień łaziliśmy do Harlemu, gdzie widzieliśmy m.in. Sekstet Milesa z Adderleyem, Evansem i Coltrane’em, a więc ten zespół znany z płyty ‚Kind Of Blue‘. (…) Jedynym klubem, do którego wtedy nie dotarłem był Village Vanguard. “ Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[101] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 50

[102] Robin Arends: Contrabassist Ruud Jacobs, een gesprek. „Ik vond het zo spannend die snaren aan te raken en de basis te leggen voor het spelen“, in: jazz’halo. https://www.jazzhalo.be/interviews/contrabassist-ruud-jacobs-een-gesprek/ (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[103] Albrekt von Konow: Bernt! „Det blir för snävt om man tänker i genrer och stilar.“ Bernt Rosengren intar en central position inom svensk jazz och är en av våra internationellt mest kända musiker. Albrekt von Konow tecknar ett intervjuporträtt i helfigur, in: Orkester Journalen, 53/2 (Feb.1985): 11

[104] Eric T. Vogel: New York – erste Station der International Youth Band. Marshall Brown lud erstmals die Presse ein, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159

[105] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 53

[106] „To była najlepsza szkoła czarnego jazzu.“ Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[107] „Had ik daar toen maar even met mijn mobiel een selfie van kunnen nemen!“ (Ruud Jacobs). Robin Arends: Contrabassist Ruud Jacobs, een gesprek. „Ik vond het zo spannend die snaren aan te raken en de basis te leggen voor het spelen“, in: jazz’halo. https://www.jazzhalo.be/interviews/contrabassist-ruud-jacobs-een-gesprek/ (aufgerufen am 20. August 2024)

[108] John S. Wilson: Overseas Stars Play In Newport. International Youth Band Combines Jazz Musicians From 17 Countries, in: New York Times, 5.Jul.1958: 13; Eric T. Vogel: Die Sensation von Newport. Das Jazzfestival 1958, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 157

[109] John S. Wilson: Overseas Stars Play In Newport. International Youth Band Combines Jazz Musicians From 17 Countries, in: New York Times, 5.Jul.1958: 13

[110] Eric T. Vogel: Die Sensation von Newport. Das Jazzfestival 1958, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 158

[111] Eric T. Vogel: Newport Rückblick, in: Jazz Podium, 7/9 (September 1958): 181

[112] Eric T. Vogel: ‚Ich habe nicht viel Neues gelernt…‘ Eric T. Vogel unterhielt sich mit Albert Mangelsdorff, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 160

[113] Eric T. Vogel: Die Sensation von Newport. Das Jazzfestival 1958, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 157

[114] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 53

[115] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 53

[116] Eric T. Vogel: ‚Ich habe nicht viel Neues gelernt…‘ Eric T. Vogel unterhielt sich mit Albert Mangelsdorff, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 160

[117] Eric T. Vogel: Die Sensation von Newport. Das Jazzfestival 1958, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 158; Bill Coss: The Newport Jazz Festival, in: Metronome, 75/9 (September 1958): 16

[118] „Z Armstrongiem było dokładnie to samo, to był cudowny, kontaktowy facet, wesolutki, przyjacielski dla wszystkich, no, ale portki się trzęsły, kiedy się z człowiekiem rozmawiało i, nawiasem mówiąc, to był chyba utwór, który najlepiej zagraliśmy, bo wszyscy byli tak spięci przy tym Armstrongu, że to inny duch w człowieka wstępował.“ (Jan Wróblewski). Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[119] Vgl. Ricky Riccardi: On the Sunny Side of the Street: 1956-1970, in: The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong, 8. December 2009. https://dippermouth.blogspot.com/2009/12/on-sunny-side-of-street-1956-1970.html (aufgerufen am 24. August 2024)

[120] Roger Guérin: Roger Guérin. Une vie dans le jazz, Aubais/France 2005 (Mémoire d’Oc Éditions): 30

[121] Michel Laplace & Félix Sportis: Roger Guérin. Monsieur Trompette, in: Jazz Hot, #593 (September 2002): 29

[122] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 48; Albrekt von Konow: Bernt! „Det blir för snävt om man tänker i genrer och stilar.“ Bernt Rosengren intar en central position inom svensk jazz och är en av våra internationellt mest kända musiker. Albrekt von Konow tecknar ett intervjuporträtt i helfigur, in: Orkester Journalen, 53/2 (Februar 1985): 11

[123] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 182

[124] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 183

[125] Bill Coss: The Newport Jazz Festival, in: Metronome, 75/9 (September 1958): 16

[126] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 183

[127] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 183

[128] Eric T. Vogel: „Das Beste aus Europa“ – aber „Ellington braucht sich nicht zu fürchten!“ Experten äußern sich zur International Youth Band, in: Jazz Podium, 7/8 (August 1958): 159-160

[129] NN: Jazz-News. Amerika, in: Jazz-Echo, September 1958: 46

[130] John Hammond, zit. nach Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 52

[131] „Joe Brown“ [= Joachim Ernst Berendt]: Die Internationale Newport Band. Ronnie Roß, Albert Mangelsdorff, Dusco Gojcowic besonders erfolgreich, in: Jazz-Echo, Oktober 1958: 39

[132] Zit. nach Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 50

[133] „Some of the musicians looked like children, others seemed poised and mature.“ (Leonard Feather)

. Zit. nach Max Jones: This world of Jazz. IYB preview, in: Melody Maker, 5. Juli 1958: 11

[134] „Solo improvisation did not appear to be one of their strong points.“ John S. Wilson: Overseas Stars Play In Newport. International Youth Band Combines Jazz Musicians From 17 Countries, in: New York Times, 5. Juli 1958: 13

[135] „…rather lumpy, unformed performances…“ John S. Wilson: The Collector’s Jazz. Modern, New York 1959 (J.B. Lippincott):146

[136] Eric T. Vogel: Newport Rückblick, in: Jazz Podium, 7/9 (September 1958): 181

[137] Horst Lippmann, Jazz Podium, Juni 1959; zit. nach Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 53

[138] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 52-53

[139] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 69

[140] Hans Salomon & Horst Hausleitner: Jazz, Frauen und wieder Jazz, Wien 2013 (Seifert Verlag): 70

[141] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 186-187

[142] NN: The Curtain Falls, in: Down Beat, 23/15 (24. Juli 1958): 9

[143] „k“: deutsche musiker nach newport, in: Schlagzeug, 3/8 (April 1958): 6

[144] Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[145] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 53; Down Beat, 2. October 1958: 11

[146] NN: Jazz-News. Europa, in: Jazz-Echo, August 1958: 48

[147] Roger Guérin: Roger Guérin. Une vie dans le jazz, Aubais/France 2005 (Mémoire d’Oc Éditions): 31

[148] NN: Youth Band Is Fretted, in: Down Beat, 26. Juni 1958: 9; korrektes Datum bei Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 51

[149] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 53

[150] Penny M. von Eschen: Satchmo Blows Up the World. Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War, Cambridge/MA 2004 (Harvard University Press): 188

[151] Rüdiger Ritter: Waffe oder Brücke? Willis Conover und der Jazz im Kalten Krieg, Berlin 2023 (Peter Lang): 464

[152] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 53

[153] Howard Taubman: Jazz, Act Your Age. When on Concert Stage, Be Professional, in: New York Times, 10. August 1958

[154] Bill Coss: The Newport Jazz Festival, in: Metronome, 75/9 (September 1958): 16

[155] „Under Marshall Brown’s leadership it played pretentiously and tediously. It had no cohesion and no point of view.“ Howard Taubman: Le Jazz Arrives At Brussels Fair; Sidney Bechet Sextet Saves the Day for U.S. in Poorly Organized Concert, in: New York Times, 30. Juli 1958

[156] „The Newport Jazz Festival and the State Department owe an explanation to the American people for this one.“ (Ralph J. Gleason, in: San Francisco Chronicle, 5. August 1958), zit. nach Nat Hentoff: Jazz in Print, in: Jazz Review, 1/1 (November 1958): 47

[157] NN: Youth Band Is Fretted, in: Down Beat, 26. Juni 1958: 9

[158] Reinhard Köchl & Peter Tippelt & Richard Wiedamann: Dusko Gojkovic. Jazz ist Freiheit, Regensburg 1995 (ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft): 53

[159] Pedro Miguel Cravinho Lopes: An Open Window to a Different World. Encounters with Jazz on Television in Portugal (1956-1974), Aveiro 2018 (PhD thesis: Universidade de Aveiro): 186

[160] Eugene Chapman: Palle Bolvig Biography. https://www.allmusic.com/artist/palle-bolvig-mn0000680665#biography (aufgerufen am 19. August 2024)

[161] Lucien Malson: Le jazz en France. Roger Guerin ou le culte de la relaxation, in: Jazz Magazine, #62 (September 1960): 42

[162] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 45

[163] Krystian Brodacki: Historia Jazzu w Polsce, Krakow 2010 (PWM Edition); 204

[164] Paweł Brodowski: Ptaszyn w Newport, 1958: Wieża Babel, in: Jazz Forum, Juli/August 1999. http://jazzforum.com.pl/main/artykul/ptaszyn-w-newport-1958-wiea-babel (aufgerufen am 17. August 2024)

[165] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 48

[166] Down Beat, 7. August 1958: 18

[167] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 49; Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 53

[168] John LaPorta: Playing It by Ear. An Autobiography with concentration on the Woody Herman Orchestra and the New York Jazz Scene in the ’40s and ’50s, Redwood/NY 2001 (Cadence Jazz Books): 183

[169] George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren. Ein Leben für den Jazz, Berneck/CH 2002 (Corvus/Zweitausendeins): 49

[170] „Joe Brown“ [= Joachim Ernst Berendt]: Die Internationale Newport Band. Ronnie Roß, Albert Mangelsdorff, Dusco Gojcowic besonders erfolgreich, in: Jazz-Echo, Oktober 1958: 39

[171] Bruno Paulot: Albert Mangelsdorff. Gespräche, Waakirchen 1993 (Oreos): 232

[172] Eric T. Vogel: Newport Rückblick, in: Jazz Podium, 7/9 (September 1958): 181

[173] George Hoefer: Newport Youth Band. Marshall Brown’s Talent Incubator, in: Down Beat, 21. September 1967: 19